Ways of fighting

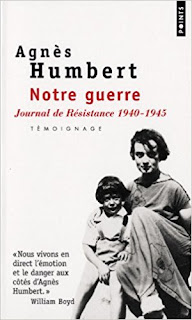

Agnes Humbert's book Resistance (originally published as Notre Guerre in 1946, it has only recently been translated into English) tells the story of the invasion of France, and early attempts at resistance. Humbert was an artist and art historian based in the Musee national des Arts et Traditions Populaires in the Palais de Chaillot in Paris. When France was invaded in 1940, Humbert and her academic colleagues formed an early resistance cell (one of the first in France), Groupe du Musee de l'Homme. They published newsletters telling the true story of the war, not the propaganda that was being fed to the French public by the Nazis and the Vichy regime. They also had connections with a network that smuggled allied airmen out of France and back to Britain.

For Humbert and her colleagues it was alternately a depressing and exhilarating time to be alive. If they were downcast by the fall of France, their work as resistants made them feel that they were fighting the battle. Inspired by De Gaulle's call to action on BBC radio, Humbert and her friends were determined to fight the Nazis to the best of their ability. What they didn't realize was that even at this early stage traitors were at work. The network was betrayed, Humbert and her friends were rounded up.

Most of the male members of the circuit were shot shortly after their arrest. Humbert spent some time in atrocious conditions in various jails around Paris, where she met up with other resistance members including the endearing and exceedingly brave Henri Honore d'Estienne d'Orves (known to Agnes by his code name of Jean-Pierre). He and Agnes were on different poles politically, but their resistance work meant that they had more in common than what divided them; D'Estienne d'Orves was an inspiration to his fellow prisoners in the Cherche-Midi prison.

Because the events following the downfall of Humbert's network happened so early in the war, her experiences were rather different to what would happen to later resistants. Humbert was sentenced to hard labour and sent to a prison in Germany. From there she was forced to work alongside common criminals, and slave labourers, primarily from Eastern Europe, in the Phrix rayon factory. The work was horrendous; prisoners went blind and were badly burned from the acid used in the making of man-made fibres. All were malnourished, beaten and tortured.

In contrast though to the experiences of many later prisoners, some Germans were kind to them. Some even appeared to be ashamed of the treatment of the women. When the war ended, following her liberation by the US Army, Humbert helped to set up soup kitchens, which fed both ex-prisoners and local Germans. Despite her often horrendous treatment, Humbert never lost her humanity, she truly was a worthy member of the Groupe du Musee de l'Homme.

The first third of the book is largely based upon Humbert's own wartime diary, kept assiduously until the day of her arrest. I'm not entirely sure how much you can completely believe in the veracity of this - how much truly was written at the time, and what was recalled from memory later (as is the case with the latter two-thirds of the book following Humbert's imprisonment).

Regardless of that though, it is a tale of astonishing courage, both on the part of Agnes herself, and of the wider resistance community. It is also a story of horrible inhumanity, which is sickening. Humbert is unflinching in her description of the sufferings that her fellow prisoners undergo. It's noticeable from this though, not least because of Humbert's unusual experience of being jailed with German prisoners, that the Nazis were unfailingly cruel in their treatment of their own prisoners too. It is also unusual to see at this stage of the war that there were still some elements of military honour among the conquerors; something that would quickly be expunged as the war deepened.

Humbert's experience though is a shining example of humanity at its best triumphing over humanity at its worst. From her own ability to keep her sense of humour under the worst of conditions, to Jean-Pierre's prison "radio" show spreading a small element of normality and home in grim surroundings. Her own experience could have left her embittered instead she chose to run soup kitchens feeding friend and foe alike. She never let the Nazis' lack of humanity stop her from being the person she was. Resistance is an astounding account of the pity of war, and, just occasionally, the glories of being human.

For Humbert and her colleagues it was alternately a depressing and exhilarating time to be alive. If they were downcast by the fall of France, their work as resistants made them feel that they were fighting the battle. Inspired by De Gaulle's call to action on BBC radio, Humbert and her friends were determined to fight the Nazis to the best of their ability. What they didn't realize was that even at this early stage traitors were at work. The network was betrayed, Humbert and her friends were rounded up.

Most of the male members of the circuit were shot shortly after their arrest. Humbert spent some time in atrocious conditions in various jails around Paris, where she met up with other resistance members including the endearing and exceedingly brave Henri Honore d'Estienne d'Orves (known to Agnes by his code name of Jean-Pierre). He and Agnes were on different poles politically, but their resistance work meant that they had more in common than what divided them; D'Estienne d'Orves was an inspiration to his fellow prisoners in the Cherche-Midi prison.

Because the events following the downfall of Humbert's network happened so early in the war, her experiences were rather different to what would happen to later resistants. Humbert was sentenced to hard labour and sent to a prison in Germany. From there she was forced to work alongside common criminals, and slave labourers, primarily from Eastern Europe, in the Phrix rayon factory. The work was horrendous; prisoners went blind and were badly burned from the acid used in the making of man-made fibres. All were malnourished, beaten and tortured.

In contrast though to the experiences of many later prisoners, some Germans were kind to them. Some even appeared to be ashamed of the treatment of the women. When the war ended, following her liberation by the US Army, Humbert helped to set up soup kitchens, which fed both ex-prisoners and local Germans. Despite her often horrendous treatment, Humbert never lost her humanity, she truly was a worthy member of the Groupe du Musee de l'Homme.

The first third of the book is largely based upon Humbert's own wartime diary, kept assiduously until the day of her arrest. I'm not entirely sure how much you can completely believe in the veracity of this - how much truly was written at the time, and what was recalled from memory later (as is the case with the latter two-thirds of the book following Humbert's imprisonment).

Regardless of that though, it is a tale of astonishing courage, both on the part of Agnes herself, and of the wider resistance community. It is also a story of horrible inhumanity, which is sickening. Humbert is unflinching in her description of the sufferings that her fellow prisoners undergo. It's noticeable from this though, not least because of Humbert's unusual experience of being jailed with German prisoners, that the Nazis were unfailingly cruel in their treatment of their own prisoners too. It is also unusual to see at this stage of the war that there were still some elements of military honour among the conquerors; something that would quickly be expunged as the war deepened.

Humbert's experience though is a shining example of humanity at its best triumphing over humanity at its worst. From her own ability to keep her sense of humour under the worst of conditions, to Jean-Pierre's prison "radio" show spreading a small element of normality and home in grim surroundings. Her own experience could have left her embittered instead she chose to run soup kitchens feeding friend and foe alike. She never let the Nazis' lack of humanity stop her from being the person she was. Resistance is an astounding account of the pity of war, and, just occasionally, the glories of being human.

.jpeg)

Comments