Lost generation

I first read Vera Brittain's Testament of Youth when I was in my mid-twenties. Already I was older than her, when her world was changed unequivocally and forever. By the time I was in my mid-thirties and holidaying for the first time in Italy with my father, many of my memories of the book had faded, though its central themes of the waste that is war, and the loss resulting from it remained.

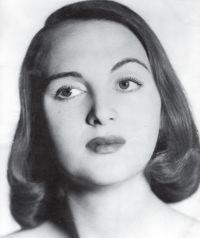

Recently, in my other life, I've posted up two music blog posts to commemorate the centenary of the Somme (see Songs of Desolation I and II). It therefore seemed an appropriate time to re-read one of the best memoirs of the First World War, and some of Testament of Youth took me completely by surprise. For those who've never come across the book before, it's an early autobiography of Vera Brittain, a middle-class girl, brought up in polite society, in the post-Victorian world of British provincial life.

Vera (who would later become the mother of the politician, Shirley Williams) was an exceptionally bright girl, who rather against the better instincts of her family, passed the entrance exam to Oxford University, in the days before women were allowed degrees, and went up to Somerville College, where she was convinced a glittering career awaited. She had been inspired by women, who influenced by the suffragette cause were convinced that there should be no limits to women's ambition or equal rights in society. Vera had already had a bit of a taste of the innate sexism of society at home, where her musical brother, Edward, who had very little in the way of academic ambition (and far less ability than his sister) was also due to go to Oxford, a move which was fully supported, and indeed expected, by both his parents.

But then events in Europe moved rapidly, war was declared, and Edward and his friends all joined up. Vera, always close to her brother, and by extension his friends, became their link and support from home. Increasingly alarmed by the way the war was moving, and the letters that she received from the front line, Vera left Somerville and volunteered as a nurse. She nursed initially in London, before moving to Malta, back to London and then to the Western Front. During this time she also fell in love and became engaged to her brother's best friend, Roland. Sadly he was killed, with Vera receiving the news on Christmas Eve - ironically the day before she was due to meet him again having believed that the break in correspondence was due to his travelling home on leave. Devastated she threw herself into her nursing work, with fears for her brother and his surviving friends growing daily.

There's a horrible feeling of inevitability to this memoir, as friend after friend falls at the Front, or is grievously injured. Brittain's world eventually changes forever when her beloved brother is killed in the closing months of the war on the Asiago plateau in Italy, a forgotten front in a bitter war. Having to rebuild her life, Brittain returns to Oxford, where she feels herself to be a survivor from a war that most of her younger contemporaries at Oxford either fail to understand, or are anxious to distance themselves from.

One of Brittain's slightly older contemporaries at Somerville was Dorothy L. Sayers, one of the first women to receive an Oxford degree. Brittain's writing about her post-war experience made me realise why Sayers' Lord Peter Wimsey can sometimes appear to be on the fringe of society. I think his role as an outsider is not just because of his aristocratic background, but is at least partly due to his own (fictional) survival as a veteran of the First World War.

Through the late 20s, despite the hardships of post-war Germany, and the Depression (there is remarkably little about the Depression in Testament for Youth), Brittain helps to build a more equal post-war society. Women have the vote - although there will be a delay in full emancipation. Sadly this was principally because if women had all been given the vote in 1918, British men would have been outnumbered owing to the fall in the male population because of the First World War. A salutary and truly astonishing statistic.

As Brittain rebuilds her life, she finally finds happiness again, while knowing that her life will never be quite the same. It's a remarkable story of survival and courage - both mental and physical; of the pity of war, and of the liberation of women. Incredibly moving, occasionally exasperating, and an astonishing and very personal glimpse into the social history of one of the most momentous periods of the twentieth century. One that would inevitably have a huge influence on the course of that most turbulent of centuries.

And what does this have to do with my Italian holiday, 10 years after my first reading of Testament of Youth? I remembered the bravery of Vera Brittain, I remembered with searing clarity the deaths of her friends, family and lover. But what I had completely forgotten was where her brother had died. Brittain's account of her quest to find his grave is very simple. No-one is quite sure where the cemetery is, Brittain, in company with a friend, travels to Vicenza (where I had holidayed), and a chance conversation there leads them to the small picturesque town of Bassano, which overlooks the Dolomites, and where they could see the level Asiago plateau, where her brother was killed.

And suddenly I was back in Italy, sitting on a bench on a beautiful July day munching bread and cheese with my Dad, and looking at an astounding view of the Dolomites, quavering blue in the distance, looking towards a level plateau - as it happens (although I didn't know what it was called, and had, in any case, forgotten the connection), it was the Asiago plateau.

Recently, in my other life, I've posted up two music blog posts to commemorate the centenary of the Somme (see Songs of Desolation I and II). It therefore seemed an appropriate time to re-read one of the best memoirs of the First World War, and some of Testament of Youth took me completely by surprise. For those who've never come across the book before, it's an early autobiography of Vera Brittain, a middle-class girl, brought up in polite society, in the post-Victorian world of British provincial life.

Vera (who would later become the mother of the politician, Shirley Williams) was an exceptionally bright girl, who rather against the better instincts of her family, passed the entrance exam to Oxford University, in the days before women were allowed degrees, and went up to Somerville College, where she was convinced a glittering career awaited. She had been inspired by women, who influenced by the suffragette cause were convinced that there should be no limits to women's ambition or equal rights in society. Vera had already had a bit of a taste of the innate sexism of society at home, where her musical brother, Edward, who had very little in the way of academic ambition (and far less ability than his sister) was also due to go to Oxford, a move which was fully supported, and indeed expected, by both his parents.

But then events in Europe moved rapidly, war was declared, and Edward and his friends all joined up. Vera, always close to her brother, and by extension his friends, became their link and support from home. Increasingly alarmed by the way the war was moving, and the letters that she received from the front line, Vera left Somerville and volunteered as a nurse. She nursed initially in London, before moving to Malta, back to London and then to the Western Front. During this time she also fell in love and became engaged to her brother's best friend, Roland. Sadly he was killed, with Vera receiving the news on Christmas Eve - ironically the day before she was due to meet him again having believed that the break in correspondence was due to his travelling home on leave. Devastated she threw herself into her nursing work, with fears for her brother and his surviving friends growing daily.

There's a horrible feeling of inevitability to this memoir, as friend after friend falls at the Front, or is grievously injured. Brittain's world eventually changes forever when her beloved brother is killed in the closing months of the war on the Asiago plateau in Italy, a forgotten front in a bitter war. Having to rebuild her life, Brittain returns to Oxford, where she feels herself to be a survivor from a war that most of her younger contemporaries at Oxford either fail to understand, or are anxious to distance themselves from.

One of Brittain's slightly older contemporaries at Somerville was Dorothy L. Sayers, one of the first women to receive an Oxford degree. Brittain's writing about her post-war experience made me realise why Sayers' Lord Peter Wimsey can sometimes appear to be on the fringe of society. I think his role as an outsider is not just because of his aristocratic background, but is at least partly due to his own (fictional) survival as a veteran of the First World War.

Through the late 20s, despite the hardships of post-war Germany, and the Depression (there is remarkably little about the Depression in Testament for Youth), Brittain helps to build a more equal post-war society. Women have the vote - although there will be a delay in full emancipation. Sadly this was principally because if women had all been given the vote in 1918, British men would have been outnumbered owing to the fall in the male population because of the First World War. A salutary and truly astonishing statistic.

As Brittain rebuilds her life, she finally finds happiness again, while knowing that her life will never be quite the same. It's a remarkable story of survival and courage - both mental and physical; of the pity of war, and of the liberation of women. Incredibly moving, occasionally exasperating, and an astonishing and very personal glimpse into the social history of one of the most momentous periods of the twentieth century. One that would inevitably have a huge influence on the course of that most turbulent of centuries.

And what does this have to do with my Italian holiday, 10 years after my first reading of Testament of Youth? I remembered the bravery of Vera Brittain, I remembered with searing clarity the deaths of her friends, family and lover. But what I had completely forgotten was where her brother had died. Brittain's account of her quest to find his grave is very simple. No-one is quite sure where the cemetery is, Brittain, in company with a friend, travels to Vicenza (where I had holidayed), and a chance conversation there leads them to the small picturesque town of Bassano, which overlooks the Dolomites, and where they could see the level Asiago plateau, where her brother was killed.

And suddenly I was back in Italy, sitting on a bench on a beautiful July day munching bread and cheese with my Dad, and looking at an astounding view of the Dolomites, quavering blue in the distance, looking towards a level plateau - as it happens (although I didn't know what it was called, and had, in any case, forgotten the connection), it was the Asiago plateau.

.jpeg)

Comments